The Most Fantastic and Intriguing Tale of the Chinese Pirate Lin Feng & the Spanish Conquistador Juan de Salcedo

The Most Fantastic & Intriguing Tale

of

the Chinese Pirate Lin Feng

and

the Spanish Conquistador Juan de Salcedo

A BRIEF HISTORICAL REMINDER OF THE TRUE ACCOUNTS OF SPAIN’S

WAR PLUNDER AND CONQUEST OF THE ISLAS PHILIPPINAS,

INCLUDING AN AUTHENTIC AND THRILLING ACCOUNT OF THE CONQUISTADORES’

ENCOUNTER WITH THE GREAT CHINEE PIRATE LIN FENG,

WRITTEN BY KEITH HARMON SNOW COPYRIGHT 1995 AND ILLUSTRATED WITH ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS

TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR HIMSELF ON HIS BRIEF VISIT TO THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS DURING

HIS AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHIC EXPEDITION IN 1993, AND ALL BEING

A TRIBUTE TO THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES AND THEIR LASTING

STRUGGLE

TO THROW OFF THE YOKE OF IMPERIALISM

*

In battle confrontation is done directly, victory is gained by surprise. Those skilled at the unorthodox are infinite as heaven and earth, inexhaustible as the great rivers. When they come to an end they begin again, like the days and months. They die and are reborn, like the four seasons.

Sun Tzu

*

With the Chinese junks that sailed to Manila early in 1574 came a snow-white mare for the conquistador Juan Maldonado and the news of war on the continent of China. Paid for in advance with gold, the mare’s delivery, in good faith, was not at all a sign of the trading times. It was a calculated gesture intended to normalize tenuous relations: from the Straits of Malacca to the Sea of the Japans, the oceans were aflame with treachery and treason. The South China Sea was boiling with samurai and serpents, conquistadors and pirates.

For the conquistadors all was business as usual: civil war on the continent of China was of little consequence. Having subjugated the Indio savages to the limits of their enlightened Spanish tempers, plagued by monsoons and malaria, uncontrollably incontinent and increasingly desperate, the Spaniards hungered to invade China and the Japans. Cruel and coldhearted, the conquistadors had become very cocky. None counted on the Chinese pirate Lin Feng.

Now, Lin Feng was no ordinary pirate. The Chinese garrison commander Wang Wang-kao later recounted to the Spaniards that Lin Feng had killed more than 100,000 Chinese with his own hands. On one day’s rampage, wrote the Imperial scribe, Lin Feng’s army massacred 60,000 soldiers and peasants. He plundered ships, burned cities, enslaved eunuchs and women. With 100,000 men, it was said, Lin Feng had devastated much of the continent of China.

“Our men were unprepared for such an assault,” wrote the surviving members of the City Council of Manila, “and very negligent. Warned two hours before of the hordes of enemies attacking the city, marching in squadrons armed with arquebuses and pikes and Mexican armor, so agile and stealthy, and in such elegant order, the way it is done in Italy, and even seeing wounded civilians fleeing the enemy, still our men took it as a joke. The Spanish did not want to believe. This negligence proved fatal.”

“Our men were unprepared for such an assault,” wrote the surviving members of the City Council of Manila, “and very negligent. Warned two hours before of the hordes of enemies attacking the city, marching in squadrons armed with arquebuses and pikes and Mexican armor, so agile and stealthy, and in such elegant order, the way it is done in Italy, and even seeing wounded civilians fleeing the enemy, still our men took it as a joke. The Spanish did not want to believe. This negligence proved fatal.”

So it was, on the 29th of November, 1574, that the well-gunned fleet of Lin Feng moored under the tropical moon in Manila bay. Juan de Salcedo, the greatest conquistador of all, was absent.

*

Now, back in the Kingdom of China, the control of the Ming emperors, in theory, extended even to the checking of dangerous thoughts. The Imperial palace employed 150,000 guards and servants, warriors, vagabonds and eunuchs. Peking was the seat of politics and war. Rice and salt were shipped from the fertile coast on the Yuan Grand Canal (c. 618 AD) – the spinal cord of the great Ming dragon.

The Ming emperors, so the story goes, were quite a spectacle indeed. Early in his reign, the Chia-ching Emperor (ruled 1522-1566) was infected by the Taoist quest for immortality and control of the empire fell into the hands of his sniveling Grand-Secretary, Yeng Sun, a shrewd but unscrupulous man under whom the empire fell into decay. Truth struck like lightning in 1543, when the palace maids tried to strangle the Emperor, and again in 1566, when, staring death in the face, the Emperor saw the great error of his life: the Kingdom of China had slid. The Lung-ch’ing Emperor (ruled 1567-1572) was an interminable whiner who lost himself in a bowl of noodles daily and, therefore, he was abruptly terminated.

The Wan-li Emperor (ruled 1573-1620) assumed the throne at the age of ten, and under sway of the Imperial Tutor and Grand Secretary Chiang Chii-cheng, China prospered once more. Chiang Chii-cheng died in 1582 however, and seizing full control that had previously been denied, the Wan-li emperor proved himself the greediest and most selfish of all the emperors of the Ming dynasty.

From 1520 to 1580 the South China Sea boiled with pirates and robber barons. The Chinese called them Wo-k’ou, “Wo” translating to Japanese and “k’ou” to pirates, but many of these so-called “Japanese pirates” were Chinese, Siamese or European.

Portuguese cannon deemed by the Chinese to be “as terrifying as good generals at the heads of armies” battered the Chinese in Canton, in 1520, even as Fernando de Magellanes first sailed the Chilean straits of Terra del Fuego. When the 10 year-old Chia-ching Emperor ascended the throne in 1522, Magellanes was already dead, speared by the natives near Cebu, his armor rusting in the salty sea.

After a battle in Kwangtung, in 1523, where the Portuguese lost two ships and 77 soldiers, the Imperial palace, on pain of death, banned emigration and trade with all “barbarian devils.” The Emperor rushed to arm China with the weapons of the invaders however, the most deadly of which “shot round bullets which were mortal to both horses and men.” By 1536, some 3000 cannon and 6300 blunderbusses armed the Emperor’s troops

The ban on trade led to smuggling as Chinese lords paid handsomely for pepper, nutmeg and cloves, rhino horn and ivory, perfumes and aromatic woods. The Portuguese wanted curios, ceramics, silk and children, and fought for them. Taxation and famine pushed Chinese peasants and fishermen from smuggling to war.

From civil war in Kyushu and Shikoku came Japanese samurai to raid the coasts of Fukien and Chekiang. Some pillaged sacred graves in northern Luzon seeking Chinese Sung (c. 960) and Yuan (c. 1279) ceramics for the Japanese tea ceremony. Wrote one contemporary of the obstreperous samurai: “Their manners were rude, their lives loose, their thoughts low, their tempers hot, their strength great and they all suspected or were jealous of one another.”

To fight the onerous Wo-k’ou, the Ming formed the Wei, regiments of 5600 men to occupy strategic coastal forts. Provincial fleets sprang up. Anyone was hired — southern aborigines, miners, salt-workers, local militia, mercenaries and Shao-lin monks – most no better than pirates themselves. Generals appointed to suppress the Wo-k’ou were jailed or beheaded for incompetence or corruption or – as happened with the most honest but envied Chu Wan (c. 1547) who committed suicide in jail — beheaded for the impertinence of their successes.

Official relations with Japan were severed (c. 1549) as piracy spread. Walled-cities and rural markets hundreds of miles inland were plundered, thousands of peasants killed. When the general Hu Tsung-hsien exterminated notorious Wo-k’ou ringleaders in Fukien and Chekiang, the Wo-k’ou flowed south to Kwangtung. It was there, to a family of freebooters and pirates that Lin Feng was born.

Lin Feng was an exceptional loser. From 1572 to 1574 he plundered the coast, gathered followers, engaged government forces, suffered defeats. He repeatedly but unsuccessfully petitioned the Ming court for amnesty. In 1572, Lin Feng had 500 men. While the Viceroy of Kwangtung beheaded 1600 pirates and sank 100 ships in 1573, Lin Feng boldly harassed the coast. By July, 1574, Lin Feng had 10,000 men, hundreds of ships. [1]

In October, Lin Feng learned from the Chinese captain of a plundered junk, returning from Manila, that the city was unguarded, the Spanish soldiers out conscripting and conquering. With 2000 men and 1000 women, with weapons to fight and implements to farm, with an armada of 62 ships, Lin Feng sailed for the Philippine Island of Luzon. His battle cry was “settle or die.”

*

Now, the Spanish were another breed of ruthless. With the arrival of the Armada of Admirante Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, in 1565, the Spaniards pumped all for spoils and secrets. The first traders encountered were the Moros, near the island of Cebu. Though wizened by earlier raids of Portuguese galliots, the Moros took the Spaniards for fools when for silver coin they sold them bars of wax with dirt centers. The Spaniards boasted of their business acumen: the Moros were warned, the silver coin returned. Bringing wax anew, the Moros told the Spaniards to again halve the wax bars. The Spaniards would not be fooled: in corners were “chunks of mangrove as heavy as lead”.

For centuries the Chinese and the Moros had traded the Pacific rim, from Siam to the Japans, Brunei to the Moluccas. Like the Spaniards, the Chinese wanted native gold, wax and spices. For these and for Spanish silver they traded fruits, nuts, flour and sugar, curios and painted porcelain, chests of embroidered silks, precious musk.

In 1570, the Spanish ships sent from Cebu to discover Manila plundered two Chinese junks without provocation, killing the merchants even as they begged for mercy on their knees. And while a Chinese colony grew alongside the Spanish town and the Indio villages in Manila, life for the Spaniards grew dimmer. Thus did the continent of China grow in the minds of the conquistadors, and the seeds of conquest grow in their hearts.

“As I gather from both Portuguese and natives who deal with them,” wrote the friar Martin de Rada, in 1569, to the King, “the Chinese are not at all warlike. All their trust lies in the multitude of their people and the strength of their walls. This could be their unmaking if invaded. God willing, they could be subjected easily. No need of many men to effect this.”

The reality of China was soon revealed to Friar Martin de Rada by a Chinese lord, his guest for six months, in 1572. “China is the largest kingdom in the world,” he now wrote, with houses of lime and stone and brick, and walled-cities protected by artillery. The Chinese “appear to be a civilized people, humble and intelligent,” though “vile and effeminate,” and “the meanest people in the world when at war, whether on horseback or on foot.” Though merchants carried weapons “of superior workmanship,” in China only the soldiers were armed: The people were forbidden weapons even in their own homes.

Hearing such news the Spaniards boasted that 300 conquistadors could overcome 30,000 Chinese. Their horses and elephants, their great walled cities – China was there for the taking. In 1572, Admirante Legazpi marked the galleon Espiritu Santo for a 1573 expedition, but Legazpi died soon after — old, poor and indebted, proof of his goodness they all said. The first Governor of Manila was not alone in his poverty.

The Royal coffers in Manila were empty, the salaries of soldiers and seamen eight years in arrears. The noblest conquistadors, like Guido de Lavazares, Martin de Goiti, Juan de Salcedo and Juan Maldonado, were granted lands with perhaps up to 10,000 Indios. Some had several islands. But the conditions on the Islas Filipinas were deteriorating. “They say that without robbing and capturing and selling slaves we cannot survive,” wrote the friar Martin de Rada, in 1572.

The Spaniards settled all with gunpowder and fire. To them the Indios were pagan Infidels who painted their ancestors and invoked the devil. The wealthier a man, the more gold and women he had, the more he offended God. Drunk on the wine of sugar cane the Indios feasted and orgied in nakedness. Some painted their bodies black all over with charcoal. They were shameless cheats, said the Spaniards, who sold baskets of rice with sand or coconut shells hidden inside. Some ate no pork but had no mosques. They killed with slingshots and poison arrows and iron spikes hidden on muddy trails. They were spirited and simple, savage and cunning, wicked headhunters who placed heads on spears outside their huts.

The Indio women were pleasant looking, the Spaniards said, but very immodest, and some, in one Spaniards words, “look like mares overfed with hay.” Others were brought in canoes for the taking, “giving both the Indio men and women a big laugh.”

The Spaniards took and took. From every village was demanded peace and tribute as the conquistadors spread over the islands like locusts. Tribes of thousands resisted, the Indios killed or driven out, thrown from cliffs, drown in the sea. The Castilas — as the Indios called them —took slaves, gold, women, cloth, rice and more women. Livestock were slaughtered, villages burned, a year’s tribute demanded in advance. Indios were taken for mines and for galleys, chained to pick and oar, flogged and beaten.

Rice was the bread of the land and the land went hungry as the Indios —hoping to injure the Spaniards – did not plant rice or millet. The Spaniards pillaged elsewhere. When again the Indios planted, swarms of locusts devoured all. For three years the locusts came. No vegetation was spared. “It is God’s will,” said the Spanish friars.

By 1573, dead of hunger and not yet dead, bodies were thrown on rafts that floated down rivers and out to the demons at sea. Fewer traders came to trade. Smallpox struck in 1574. The Spanish locusts ravaged all. Plagued by an epidemic of violence and sin, the Religious refused to hear the confessions of the conquistadors.

“Castilas,” shouted an Indio from a tall palm tree one night, his fortified village surrounded by 100 harquebusiers in helmets and coats of mail. “What do you want? Why do you make war on us? Why do you ask us to pay tribute? What do we owe you? What good have you done us or our ancestors? We call on our gods and on yours as witnesses, they will judge the abuses and injustices you commit against us.”

The village was burned to the ground.

Anonymous reports reached the Royal ears: “The Indios have come to identify Castilas as robbers, usurpers of what is not theirs, men with9out a word of honor, cruel individuals who spill human blood, persons dirty in the flesh. They see with their own eyes that Castilas do not spare even friends, rather they attack and maltreat and force them, they violate their homes, their wives and daughters, and their property.”

“Fix it up,” yawned the Spanish King, a goblet of palm wine in one hand, a gold scepter in the other, “correct these Spaniards and reform their bad habits.” To the Manila officials: “I am sending a new Governor. The following islands and towns are declared seats of government. Send the captured slaves to the silver mines of New Spain,” the King boldly decreed.

“Build a hospital,” the King ordered, “treat both Spaniards and Indios: we are told that many are sick, many have died. Do not take Indios from one island to another. Befriend the Chinese. Watch for a chance to preach the Holy Gospel and other good objectives in China. Keep me informed.”

Such were the Royal decrees of 1574.

*

On July 26, it was business as usual. The galleon San Juan departed Manila with the latest news and plunder for His Sacred Catholic Majesty, Don Felipe II. Kissing his Royal hands and feet, the King’s vassals sent a meager four tons of cinnamon — San Juan was built not for trade but to fight and run — a dash of pepper, a porcelain bowl, fourteen gold earrings and four daggers with gold hilts. To Her Majesty, the Queen, went jewels and pearls and flasks of cinnamon water. For His Newborn Highness, Prince Fernando, a gold crown, two gold chains and four gold daggers used by the natives.

San Juan carried a letter from the Governor of Manila, Guido de Lavazares, asking the King for 500 men of war, for gunpowder and ammunition, for 50 sawyers and blacksmiths and shipbuilders from the black slaves of New Spain, for men of the Church. Lavazares described hardship, justified actions, countered the “opinions” of the Religious, explained recent changes in bilateral relations with the Chinese. “Seeing the good treatment they have always had,” he wrote, “the Chinese come every year and increase their trade. They take much of His Majesty’s gold.”

To the Chinese traders Lavazares decreed the sovereignty of the King and the exclusivity of conquest. “No longer will you be allowed to sell harquebuses and gunpowder to the natives,” he decreed. “The taking of slaves is prohibited, since I am told that slaves are offered as sacrifice. Beware the selling of bales of silk cloth where weeds are discovered inside. Next year you will pay import tax.”

Thus warned, the Chinese departed.

But from the blood of their desperation the Spaniards drank the idea of China. The bamboo and grass huts, the glass oven heat, disease and typhoons and famine and those horribly “disrespectful” natives – China was the escape. Chinese traders were petitioned to give passage to the Religious. “Our possessions would be confiscated,” said the traders, “we and our wives and children would be killed if we brought a Spaniard or any other alien to China.”

China would not wait for the Spaniards to come: In the moonlight on 23 November 1574, a large fleet of well-gunned ships was sighted by Juan de Salcedo, Captain of the Infantry, 70 leagues north of Manila at the Villa Fernandina. The pirate Lin Feng had arrived.

*

At the Villa Fernandina, on Luzon, the great conquistador Juan de Salcedo waited. With 80 men, Salcedo had been sent north, to Ilocos, in April, to found and settle the Villa in honor of the Infante, Prince Fernando, and to pacify the natives, the fiercest in the islands, who wore “corselets of iron and buffalo hides and helmets embellished with fish bones and shells.” Salcedo was after the gold of Ilocos.

Now, Juan de Salcedo was no ordinary conquistador costumed in cold steel. A daring and hardworking soldier, he was born of the legitimate union of Pedro de Salcedo, son of Juan de Salcedo, discoverer and conqueror of the Kingdoms of New Spain (the Americas), and Dona Teresa Garces, eldest daughter of Admirante Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, discoverer and conqueror of the Islas Filipinas. War ran cold in Salcedo’s blood.

Arriving in 1567, commissioned Captain of the Infantry in 1568, Salcedo stood with Admirante Legazpi, Guido de Lavazares, Juan Maldonado and Martin de Goiti when the Portuguese attacked Cebu. Salcedo and Martin de Goiti conquered Manila. Salcedo begged his grandfather, Legazpi, to let him explore and conquer Luzon. Funding the expedition himself, building eight ships, sailing 200 leagues around the island, crossing raging rivers and skirting volcanoes, surveying the mines of His Majesty’s richest provinces, pacifying the savage natives, Juan de Salcedo – not yet twenty-five years old – was undoubtedly the greatest conquistador of them all. The mere sound of his name burned the ears of the Indios.

Nor was Salcedo an ordinary murderer. No other conquistador was so often and so highly recommended to the King. Bound by the cross to truth, even the most pious Religious revered Juan de Salcedo as a good soldier and a good Christian who was loved and deserving. “Though at the outset he was very young and I was displeased with him,” wrote Governor Lavazares, in 1574, “afterwards I recognized his quiet strength of purpose. He has excelled in all he has been asked to do for His Majesty’s service.”

Thus did Juan de Salcedo prepare for war with the unidentified but approaching Chinese ships. He and his men watched from afar as the pirates pillaged a galley returning with the essential supplies for the Villa: the cannon were taken, the Indio slaves killed, the galley burnt. But the unidentified armada passed by without a fight: Lin Feng wanted Manila. Onward did the Chinese sail.

Horrified at the obvious intent of the mysterious fleet, and with 59 harquebusiers in seven small boats oared by Indio slaves, Captain Juan de Salcedo sailed the high seas in a race to defend the imperiled city of Manila. He would arrive one day late.

Lin Feng raided and conscripted along the coast of Luzon until 29 November, when the armada moored off Cavite, eight leagues from Manila, and a force of 200 men in native bancas sailed under the moon to attack at dawn.

“It was God’s will that they were hit by a gale which did not blow in this city,” wrote the dispirited City Councilors who escaped with their tongues. “Many ships were lost. The attack came at ten in the morning.”

“It was God’s will that they were hit by a gale which did not blow in this city,” wrote the dispirited City Councilors who escaped with their tongues. “Many ships were lost. The attack came at ten in the morning.”

That such a force could attack Manila was blasphemous. Soldiers were collecting tribute or fortifying Villas elsewhere, many were sick. The city was “dirty and unhealthful,” a swamp of intolerable heat, where canoes floated from house to house after a rain, where drinking water was brown. Fort Santiago built of wood in 1570 by then Governor Legazpi [2] had collapsed, cannon lay unmounted on the ground.

On the feast day of Saint Andres, the pirate Lin Feng ate the Spaniards for breakfast.

“The Spaniards made fun of those who brought the news,” wrote the City Council, “saying the Borneyes who were known to attack this city could not come. Most skeptical were the Maestre de Campo, Martin de Goiti and the Governor, Guido de Lavazares.”

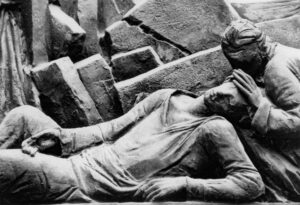

Martin de Goiti was first to die. In bed with his wife, asleep, awake, sipping wine for breakfast – the accounts differ. Meeting no resistance the pirates entered his house killing servants and soldiers, all but his wife, Lucia Sanchez, who escaped with her cheek slashed to the neck. Wrote one witness: “They killed Martin de Goiti and burned him, after cutting off his nose, his ears, his genitals and upper lip with the mustache.”

Led by a Japanese samurai the pirates plundered a path to the Governor’s house. After a three hour “skirmish” with Spanish forces the pirates turned back, robbing and burning houses in an orderly retreat to their ships. “It was God’s will that the enemy retreated,” wrote the City Council, “they could have killed us all in their fury.”

The first day of December was blessed with miracles. As the desperate Spaniards dug in behind sandbags and crates, the pirates rested. Early that evening, after six days and six nights and 180 miles on the iron waves of monsoon, Captain Juan de Salcedo arrived with his 59 harquebusiers. When later that night the armada moored off Corregidor Island and traded volleys with shore, half of Lin Feng’s ships were lost. At sunrise, with 1000 pirates, Lin Feng hit the beach. The natives came behind him.

“There were 5000 rebellious natives with raised flags,” wrote one Spanish survivor, “beheading and killing the servants and slaves who were fleeing this city in fright.”

Entrenched in their meager fort with their mighty harquebuses the outnumbered Spaniards fought like frightened rats. After eight hours the Chinese penetrated the Royal houses, where women and children and casualties were taken, but the Spaniards rallied and drove them back. When Lin Feng signaled his ships for more men, and more men came, the Spaniards ran back to their hole. But “it was God’s will to favor the Christian camp,” wrote Governor Lavazares, and with superhuman effort we withstood the attacks.”

Sounding bells and whistles and marching in columns through the town, robbing and burning and killing, Lin Feng withdrew to the beach for the night. There were 600 Chinese dead and hundreds wounded. In terror the Spaniards waited. At dawn, Lin Feng returned to his ships, hauled anchors and sailed into the sunrise. Manila was burning.

Rebellion spread through the islands like smallpox and up to 60 Spanish soldiers and thousands of Indios died. Seeing the Spanish victory, the Indios again pledged their loyalty, and soldiers were recalled to Manila to build and arm a fort. But churches were desecrated, icons destroyed, hogs and goats beheaded on the altars, boiling water poured on the friars – this was only fair, shouted the Indios — their spirits broken by the Spanish victory — since the friars baptized with cold water. Clothes and food and gunpowder were scarce.

From Pangasinan, 50 leagues north of Manila, an Indio loyal to the Spaniards brought the dreaded news: the pirate Lin Feng was building two forts at the mouth of the Agno River.

Four months of worsening hardship later, two Spanish galleons and 67 native boats sailed forth from Manila with 250 soldiers and 2500 native conscripts to Pangasinan Bay. There, on 21 March 1575, the indefatigable Juan de Salcedo, now Maestre de Campo, held a Council of War. So began the four-month siege of the tyrant Lin Feng and, inadvertently, the King of Spain’s opening to China.

*

It was a dark day for Lin Feng. Taken by surprise, his entire fleet was burnt and sunk. The Spaniards took one fort, killing 200 men, capturing 70 women and children, burning houses. The tyrant’s main fort, built on a rise between two rivers, armed with Spanish cannon of superior range and trajectory (pillaged from the Spanish galliot off Ilocos) was impregnable: Spanish artillery and stone-throwers battered it; soldiers waded the river and stormed it; men and artillery were lost to it; only once did Salcedo attempt to take it. Instead, he decided, they would starve the pirates out. Lin Feng would not have it.

“Many days the Maestre did not know where the pirate was,” wrote one soldier. “One night he left with 25 soldiers to wait in ambush, but the shrewd tyrant had many sentinels and spies and he ambushed and encircled the Spaniards three times. Not satisfied with this, he set up, for all to see, 500 harquebuses at the entrance to his fort.”

The pirates repeatedly sallied forth to attack the Spaniards. Friendly Indios brought food and firewood. Spies and double agents proliferated. Thus in earnest did the commanders Juan de Salcedo and Lin Feng wage a guerrilla war in the tropical forest: It was bloody, protracted and horrible. No shield guarded against ambush or disease.

-

Two indigenous Batak men on the island of Palawan, Philippines. Photo courtesy of the Government of the Philippines.

*

Now the Chinese garrison commander Wang Wang-kao was tracking Lin Feng like a dog. With two Imperial war-junks he arrived at Pangasinan two weeks into the fray. Assuring Wang Wang-kao of Lin Feng’s eventual defeat, Juan de Salcedo sent him to Governor Lavazares, in Manila, who received him with the grace of the aging dignitary he had become. Lavazares pledged allegiance against the pirate Lin Feng and delivered the Chinese women and children who had been kidnapped by Lin Feng and liberated by the Spaniards.

Sufficiently impressed — and promising great reward for Lin Feng’s head — Wang Wang-kao departed Manila on 12 June 1575, anxious to inform the officials of Fukien and Chekiang of the pirate’s imminent defeat. On his ships went the first Spanish mission to China: two friars and four soldiers [3] bearing presents and letters to the Emperor. Thus did the door to the House of China decisively swing open.

*

The first Spanish mission to China was documented in detail by the industrious scholar and Holy spy, the friar Martin de Rada. The ships landed at Amoy and Chang-chou. The Spaniards were draped in silk and carried on palanquins through “throngs of people we could not deal with,” wrote Rada, who “swarmed up walls and roofs of houses and sometimes stayed staring until late in the night.” Squadrons of Imperial troops marched them, sounding drums, trumpets and cornets, every soldier and servant on a horse with coolie to look after it. A banner at the fore announced the guests of the Emperor, ordering that every man and woman attend to their needs at the expense of the royal exchequer.

To Friar Martin de Rada, China was “the most populous country in the world.” Houses grew thicker than weeds on the shores of rivers. Every crack and crag of land was sown with seed. Markets were walled with fish, cities walled with marble, cut by canals. Garrisons of 5000 soldiers presented arms, mandarins and magistrate’s held banquets in their honor. Taken overland to Foochow, they were humbled at the feet of the Governor of Fukien, Liu Yao-hui. Resisting the ceremonial “three kneelings and nine head-knockings,” the soldiers complained. (They later reported their impression that Wang Wang-kao and the Chinese interpreter had told lies about them.) The Viceroy “asked many and very curious question,” wrote Friar Rada. “He was much astonished at our replies, since the China nation is so presumptuous that they consider themselves to be the first in all the world.”

The letters asked that a port in Fukien be designated for Spanish ships to trade safely, as the Portuguese had at Macao [4], and permission for the friars to remain in China to preach the Gospel freely. Liu Yao-hui forwarded these requests to Peking, explaining his lack of authority, promising many favors for the head of Lin Feng.

“The said tyrant has no one to help him nor give him food,” wrote Manila’s Governor Lavazares to the rulers of China. “In my opinion he will be captured or killed in two months. If captured alive he will be taken to your presence and if dead only his head preserved in salt will be sent.”

Lin Feng was not one to lose his head. No ships and no sleep, four-months under siege, an exceptional loser, Lin Feng was not lacking in audacity and genius. He was greatly underestimated by his adversary, the conquistador Juan de Salcedo. He was a master of camouflage and engineering. He distracted Salcedo with unorthodox guerrilla tactics while his own men sailed upriver in small boats and floated logs to build big boats. In the darkness on 4 August 1575, the pirates sailed in 37 ships from secretly dug canals and rammed the Spanish barricade on the Agno River.

Lin Feng sailed by the light of his victorious soul.

The wind which filled the sails of Lin Feng’s ships soon carried rumors to the ears of the garrison commander Wang Wang-kao: The plague of Lin Feng was again devastating coastal China. Ordered to investigate, Wang Wang-kao sailed with ten warships and 500 soldiers on 14 September 1575. With him went the Spanish mission and gifts for the governor and Captains in Manila. From his ship he pointed to Wu-hsu Island in the Bay of Amoy, the trading post to be given the Spaniards if all went well.

All went badly. After two months of typhoons on the high seas the Imperial armada arrived in Luzon to find Lin Feng gone. Wang Wang-kao threw a tantrum. To make matters worse, the new Governor had arrived from New Spain. He was impertinent and obstreperous. Indignant, disgusted at the loss of Lin Feng, his faith in the Spaniards shaken, Wang Wang-kao insisted that the gifts from the authorities of Fukien go to Lavazares.

“The Chinese were so greatly displeased with thenew Governor,” wrote the old Governor, Lavazares. “They were forced to give more than they had brought and received little affection and meager gifts. They brought sixty bales of silk, two umbrellas, sunflowers, a chair of rare wood, and out of appreciation, a horse. The discovery of China was made upon my orders, but Governor Sande has appropriated these gifts for himself. These things are mine and they belong to me.”

*

Doctor Francisco de Sande arrived in Manila, in August, just two weeks after Lin Feng’s escape. Some said he did greater damage to the Spaniards than Lin Feng. He was an overzealous administrator with a vitriolic tongue. He was hated by all but the most corrupt. He ruthlessly investigated the most loyal. He confiscated properties and titles. He forbade the former Governor, Guido de Lavazares — whose grace and chivalry had earned the respect of Wang Wang-kao — all communication with the Chinese. And he was a military idiot.

The Imperial Chinese troops overstayed their welcome, many in the homes of Spaniards. On 4 May 1576, after six months of diminishing provisions and increasing animosity, Wang Wang-kao left Manila for Fukien. With him — or forced on him by the impudent Dr. Sande — went the friars Martin de Rada and Augustin de Albuquerque. With him — to validate Lin Feng’s demise to his superiors —went every human skull and skeleton his soldiers could scrape up from the tropical battlegrounds. Wang Wang-kao was discontented and hostile.

Wrote one soldier of the departed Chinese: “The Sangleys are big-bodied, brawny, scant-bearded, slit-eyed, broad of forehead and not bad or unpleasant looking. They have an alphabet and print but the characters are not so good. They have books on philosophy, astrology, music and the arts, physiognomy, even on mechanics. They are very dissolute in their food, more so in their luxurious way of living, and, obviously, they are great sodomites.”

The door to the House of China swung briefly in the wind of Wang Wang-kao’s Imperial despair. To return to China without the head of Lin Feng was to gamble with the Imperial whim. Further, there was not one valuable present to bribe the Imperial greed. From this we can infer the fate of the Chinese garrison commander sent to Manila to capture Lin Feng: Wang Wang-kao, quite literally, lost his head.

En route to China he killed the Chinese captured by the Spaniards so that none could tell the truth about Lin Feng. On an island in the province of Ilocos a conquistador patrol found the friars Martin de Rada and Augustin de Albuquerque. Said one soldier, “they were tied to a tree, naked and bleeding.” Thus was the door to China decisively slammed shut.

The fate of the pirate Lin Feng is uncertain. One historian has it that Lin Feng harassed the coast of China until 15 January 1576, when the Fukien naval forces of Hu Shou-jen sunk twenty of his ships, and that he fled to Siam, where he and 1712 followers were pardoned, 688 prisoners freed. It is said that Lin Feng never again sailed in the South China Sea.

“Regarding the conquests of China,” wrote an embittered Dr. Sande, the new Governor of Manila, “it should be done resolutely if your Majesty is to be served. It is not right to hesitate. With a few armadas this land could swell with enough men to overthrow and easily take possession of China.”

But settlers and soldiers would not come. Malaria, Denghe fever, intestinal parasites and venereal diseases were all, most likely, amongst the maladies of the Islas Filipinas. Reports had reached Spain and Mexico of the great hardship and scant profit for those who risked their lives on the track of the Manila galleons. The loss of the Espiritu Santo, on 20 May 1576, confirmed the horrors: the galleon was shattered by typhoon on a reef near Ilocos and “those who did not drown were pursued by the natives and pierced with lances.”

“And the land is so little conquered,” wrote Don Sancho Diaz de Caballos, a new arrival, “that only one league from this city hostile enemies come to kill soldiers and pierce them through with spears as a pastime. And the Spaniards are depreciating and content themselves with vain words saying from this distance that every mere man can kill all of China and one out of every two, I swear to God, claims more strength than Hercules.”

So demanding were the Islas Filipinas on the conquistadors however, that even the proverbial Hercules could not sustain forever: On 11 March 1576, Juan de Salcedo, rumored to be the greatest conquistador of them all, died mysteriously on route to the gold mines of Ilocos in northern Luzon. Not yet 30 years-old, Salcedo, the Maestre de Campo, some said, was poisoned. Buried on a mountain, fire over his grave, Juan de Salcedo instructed that his estate be returned to the Indios.

“That is what all those who die here do,” wrote the conquistador Don Sancho Diaz de Caballos, “because that is the only way they can be absolved of their great sins. And this is another misery of the land – that they live without really living. In the end, I think, the devil comes to take their souls, and Saint Anthony to take their clothes.” ~

[1] From the Ming Biography of Lin Tao-ch’ien, another pirate, we find that the ancient Chinese Ming shih-lu confuses Lin Tao-ch’ien with Lin Feng, believing it was Lin Tao-ch’ien, not Lin Feng, who attacked the Spaniards in 1574. This is the take by historian Eugene Lyon, Ph.D., whose “Track of the Manila Galleons,” in the National Geographic, reads “Lin Tao Kien…attacked [Manila] in 1574.” Per the Ming Biography of Lin Feng, by Jung-pang Lo, both, apparently, have it wrong. At some time in 1574, Lin Feng may have defeated and absorbed the forces of the pirate Lin Tao-ch’ien. But it was Lin Feng who attacked Manila.

[2] The walled city of Intramuros, in Manila, was not built until some time after 1580.

[3] Members were obviously chosen very carefully for their intellect and experience. The friars were Martin de Rada and Jeronimo Marin. The soldiers were Miguel de Loarca, an old companion of Legazpi, Pedro Sarmiento, Juan de Triana, Nicolas de Cuenca. See C.R. Boxer, ed., South China in the 16th Century.

[4] The Portuguese officially established bases in Macao 1557; and in Nagasaki, Japan in 1571.

[5] The primary research for this writing came from the three volume (translation) set: The Philippines under Spain: A compilation and Translation of original documents. Book I (1518-1565): Voyages of Discovery [con dedicatoria], by Virginia Benitez Licuanan // Jose Llavador Mira (editores),