This project involved many people whose courage, resilience, kindness and determination cannot be overstated. Some of the names are changed, some redacted, to protect them from possible targeting by agents of the Burmese government. Along with the images of survivors I have gathered testmonials about the vioelnce, including dates of military operations, and the results of them; forensice evidence; the dates and places where atrocities occurred, and sometimes the names, ranks, or official positions of some of the perpetrators of atrocities.

Rohingya: We Prefer to Call it Burma

Cox's Bazaar, Bangladesh

A Rohingya girl stands on the fringe of the world’s largest refugee camp, known as the Balukhali-Kutapalong expansion site. In 2017 more than 730,000 Rohingya, mostly Muslim, were forced out of Burma and into neighboring Bangladesh. This was a huge and unprecedented exodus, where the newer Rohingya refugees joined some 250,000 Rohingya that over the previous 15 to 20 years had fled Burma and established themselves in far eastern Bangladesh. Some 13 camps have evolved, with approximately 1 million Rohingya refugees effectively declared ‘stateless’ by the military government in Burma.

The indigenous Rohingya people traditionally lived in the region comprised of Rakhine State, in Burma, and several large districts in eastern Bangladesh, including Cox’s Bazaar, Chittagong, and Bandarban districts. The Burmese government has revoked their citizenship and declared them occupiers and land-grabbers claiming that they all historically lived in Bangladesh, though there is a long and well-documented history of the Rohingya’s traditional ethnocultural history on both sides of the international boundary delineated in the colonial era.

The monsoon season in Bangladesh (Southeast Asia) brings heavy rains and high winds, electrical storms, frequently evolving into typhoons, cyclones or hurricanes. The Rohingya refugee camps like this one, Balukhali, evolved on geographical terrain that was formerly heavily forested with tropical species: large dipterocarps, mahogany, bamboos and palms. The high rate of influx and large refugee population density—with the people’s concomitant desperate struggle for survival (food, firewood, shelter)—caused the forests to be denuded of most all vegetation, creating steep hills that become treacherous and muddy, with high potential for landslides, and ravines that quickly and dangerously flood.

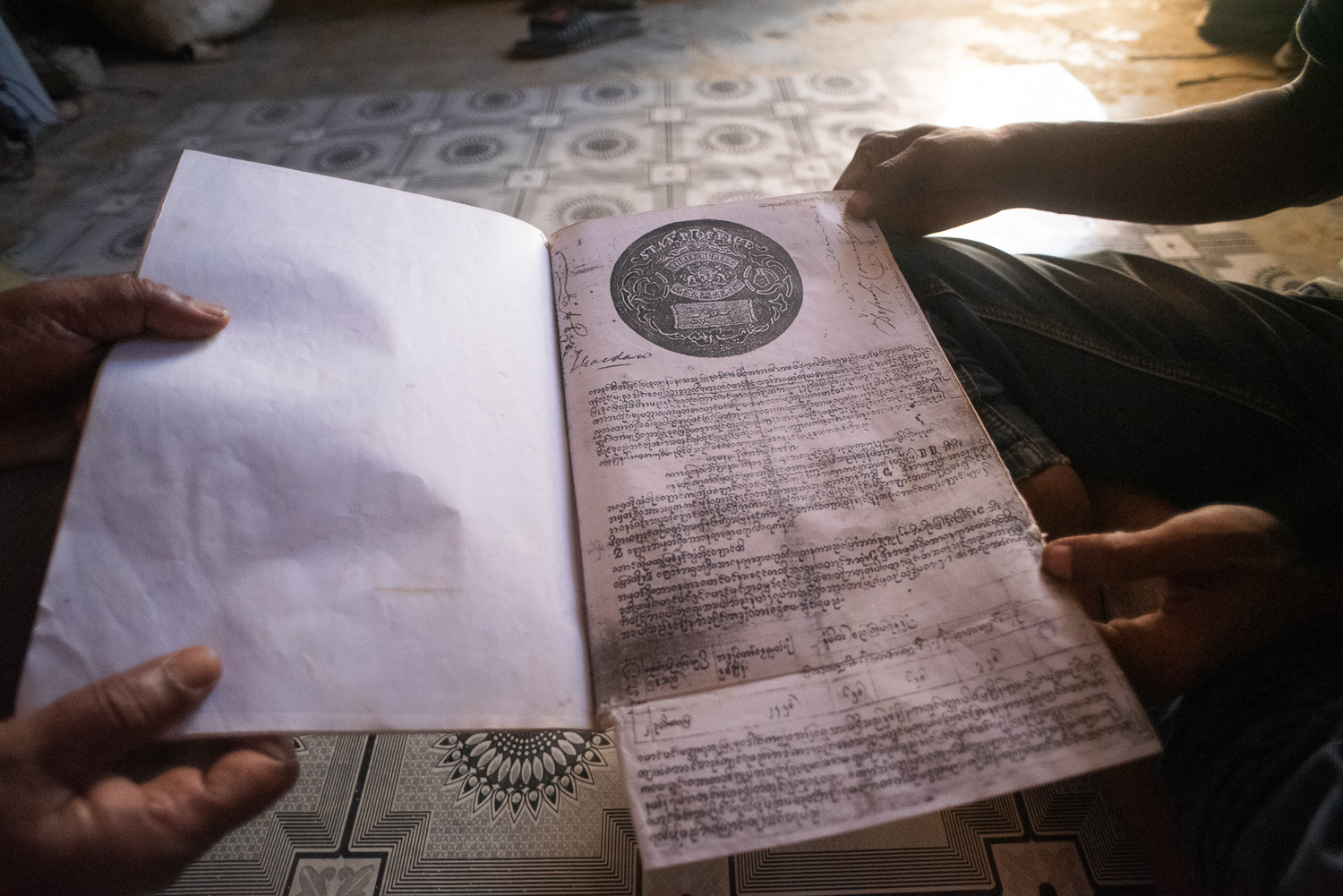

A Rohingya child casts a curious glance at a soldier of the Bangladesh Special Forces (RAB) who is standing guard, with sub-machine gun, during a special disaster-preparedness exercise at the Balukhali refugee camp. The Bangladesh army got involved in the Rohingya situation very early, providing many soldiers to manage and register all the refugees. Many of the Bangladesh soldiers are themselves suffering, due to low salaries, authoritarianism, poverty and lack of education. The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) is the Bangladesh army’s special forces branch that is known for committing serious abuses against the Bangladesh population.

A young Rohingya man (16) working under the scorching hot sun on a steep deforested hillside of the Balukhali camp uses a Bangladesh pick-adze to cut a channel in advance of the imminent monsoon rains. Fear of landslides was widespread, and remains so, as many of the Rohingya refugees continue to reside in substandard rudimentary shelters made of bamboo and plastic tarps, many of which were erected hastily and on steep inclines (in any case). The week of 14-18 May, 2018, a minor landslide due to a cyclone killed five Rohingya refugees. In May of 2017—prior to the massive Rohingya refugee influx of August and September 2017—typhoon Mora battered coastal villages of the Cox’s Bazaar district, killing at least six people, and completely destroyed more than 10,000 huts in the Balukhali-Kutapalong refugee camp.

A Rohingya elder, another survivor of genocide, spends what she expects will be her last days resting in a bamboo hut at the Uchiprang refugee camp, 15 May 2018. Her husband was killed by the army at Hascharbil village, in Burma’s Rakhine State. She fled the genocidal violence, arriving in Bangladesh in September 2017. She is worried about landslides. “We have cried so much in the last 9 months,” she said. “Many [women] saw their husbands killed by [the Burmese army] slitting their throats.”

A fishing vessel—heading out to sea—navigates the Naf River just off the coast of the Maungdaw district of Burma’s Rakhine State. Maungdaw was the site of massive genocidal violence, with widespread atrocities and scorched earth destruction of villages committed against the Rohingya by the Burmese military. Many Rohingya were forced to flee to the shores of the Naf River and seek some kind of transport out of Burma. The closest prospect was the Cox’s Bazaar district of Bangladesh, just across the Naf River, but many Rohingya have been forced further adrift at sea, eventually landing in Malaysia, central or western Bangladesh, eastern India.

The Naf River’s average depth is 128 feet (39 m), and maximum depth is 400 feet (120 m). Some Rohingya have been forced to swim across the Naf River, others subject to extortion by brokers demanding high fees.

December, 2019: A Rohingya boy carries a sack of provisions over the peak of a hill at Camp 13, the southernmost Rohingya refugee camp in the Cox’s Bazaar district. The tower in the background is an ‘elephant watch tower’ constructed to enable volunteer sentries to hold overnight vigils on watch for elephants coming out of the forest. Wild elephants have encroached on the camp, destroying huts and terrorizing residents: in 2018 a 15 year-old boy was trampeled and killed by a wild elephant.

1 December 2019, Kutapalong Camp: Muhammed Salam (45) tells his story:

Muhammed Salam was a landholder and all his lands in his daung (village) Yamachang were confiscated by the soldiers in 2014. He alleges that on 9 October 2016 he was beaten mercilessly by the Burmese military: they accused him of killing a pig, knocked out three of his teeth, broke his left leg, stabbed him. The military started an ‘operation’ on that day, he says: many villages were torched, many Rohingya killed, many women and teenage children were gang-raped by the Burmese soldiers. He reveals the scars on his body. His son was disappeared. He names generals, other commanders, and soldiers responsible for atrocities. While fleeing to Bangladesh on 25 August 2017, he and his wife witnessed over 35 Rohingya being shot at Kunshipying, a small village on the Burmese-Bangladesh frontier. He names seven victims, and their ages. He also witnessed Burmese soldiers shooting Rohingya as they tried to flee across the border at the Naf River.

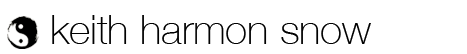

‘Muhammed X’ displays a primitive but accurate map of his village, Bawli Bazaar, with his home on it, that was burned to the ground by the Burmese military in late August and early September 2017. ‘Muhammed X’ drew this map from memory after his arrival at the Baggana refugee camp in the Cox’s Bazaar District of Bangladesh on 19 September 2017. ‘Muhammed X’ was born in Bawli Bazaar on (date redacted), 24 miles from the hard-hit Maungdaw town, and he lived there all his life, more than 60 years.

“Over the years the [Burmese] government has launched many different military-intelligence operations targeting Rohingya people,” ‘Muhammed X’ said.

Bawli Bazaar village was burned on 25 August 2017. The red-roofed building was a mosque. The blue building with the flag was a high school. Inside the triangle, a hospital. The river is Phuma Creek. The village was leveled, bulldozed to ‘zero level’.

A member of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) consents to be photographed, donning a mask for anonymity, during a limited interview at the Kutapalong camp in December 2019. “I became a member of ARSA in 2012,” he says. “We have a purpose. The Rohingya have been persecuted by the Burmese government for decades.That’s why we decided to take up arms, to protect ur brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers. Our sisters have been raped in front of relatives, and our brothers are killed in front of villagers. We never get peace in [Burma]. So we decided to take our rights back. Rohingya have lived in Burma for centuries. We are the indigenous people of Burma.”

In 2016, ARSA destroyed a Burmese immigration department headquarters [called NASAKA]. ARSA allegedly killed 20 police officers and confiscated some weapons. Before this ARSA attack there was a long history of ethnic violence, random and premeditated, by the Burmese military against Rohingya. The military government points to the ARSA attack as justification for their genocidal violence, claiming ARSA are responsible for the troubles in the Rohingya community and beyond. Rohingya leaders—and ARSA—claim the Burmese military has manufactured evidence of Rohingya violence that never happened.

2 December 2019 Camp 13: Muhammed Wares (55) (pink shirt), Ali Muhar (40), and Noor Kobir (~27) of Bathidaung township, Rakhine State, describe the long history and patterns of violence, targeting the Rohingya, that qualify the genocidal intent of the Burmese military, including what they described as a planned policy of limiting Rohingya births. They also described personal experiences with family members being beaten, raped, killed or disappeared, starting—for them—as early as 1994. Muhammed Wares described mass rapes.

They outlined the escalation of violence of August 2017, listing names/ages of people they saw killed. They claim the military and police attacked with RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades). They named the battalions that soldiers came from, names of the commanders.

While crossing the border to Bangladesh they saw Rohingya being shot, people “slaughtered with knives and spears.” Ali Muhar alleges he saw “about 400 Rohingya people massacred in one day”: the residents of the villages of Tula Tuli and Myingyi. He fled across the border in a small boat across the Naf River.

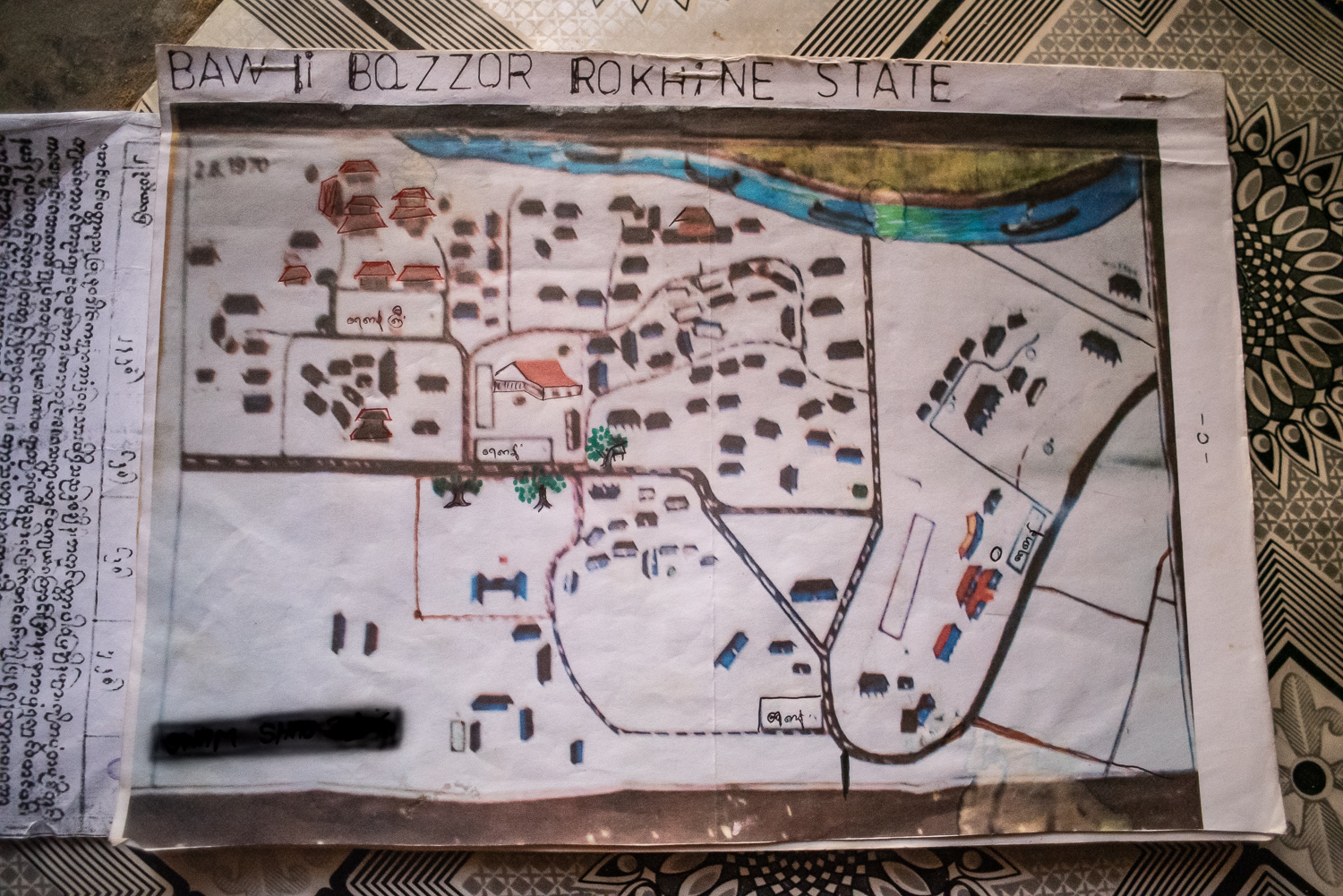

They also produced the various ID cards that establish a clear pattern of manipulation, showing how the state used ID cards to control and deny citizenship to the Rohingya.

The Rohingya have limited opportunities to leave the densely overcrowded refugee camps. During the rice harvest, however, Rohingya are allowed by the local Bengali population—and the longer term, previously assimilated Rohingya refugees—to participate in the winnowing of the crops, sharing the labor to produce bushels of naked rice for storage or sale at market.

“Sweet Dream” reads a large billboard erected on a plot of real estate forcibly seized by a powerful land speculator from Dhaka. Land is premium in the Cox’s Bazaar and Tecnaf districts of far eastern Bangladesh, near the Burma border, where the flood of refugees has overwhelmed the natural resource base and drastically altered the economic and cultural realities of life for millions of people. The poorer locals—both Bengalis and Rohingya who have long since been settled in the Tecnaf/Cox’s Bazaar districts here—are often powerless in the face of real estate corruption and land theft. The billboard is declaring new private ownership of what has long been communal land belonging to indigenous people.

Waiting for others to join him to perform the early evening prayers (on a blue tarp he has spread out under the palm trees), a Rohingya man looks out over the sea, the Bay of Bengal, at sunset near Tecnaf, a district far south of the city of Cox’s Bazaar. Many Rohingya who fled Burma years before the 2017 violence have effectively assimilated and put down roots amidst the local Bengali population up and down the coast here. The coastline of the Cox’s Bazaar district offers the longest contiguous beach in the world, and the government of Bangladesh and big business tycoons have begun a ruthless development of the coastline for tourism. The Rohingya know that Rohingya people are being trafficked by profiteers, and suffer injustices, if not death, while making the sea journey out of Burma, or while trying to escape the hopeless aimless life of a Rohingya refugee trapped in the overcrowded camps.

At sunset near Tecnaf, only a few miles from the sprawling refugee camps, indigenous Bengali fishermen stand vigilantly watching the waves for the silver flash of schools of fish driven into the shallow tidal flats by larger fish on the hunt. Fish are a premium food for hungry refugees, and the competition for fish and fishing is fierce amongst the local population and the refugees.

Another day, another sunset, half way down the coast from Cox’s Bazaar to Tecnaf, just a few miles west of the Rohingya refugee camps. Boats like these built by the resident indigenous peoples—including Rohingya who have long since assimilated into this area of Bangladesh—are sometimes used to rescue Rohungya refugees, get them out of Burma to Bangladesh across the Naf River; but sometimes they are used to traffic Rohingyas for the sex trade, or purely to extort money from them, preying on their desperation and their entrapment y the Burmese military and their subsequent flight in search of security, freedom and survival.

Gwendolyn Atwood

Such courage and clarity are not met often yet on this planet. Your fearless witness is a gift to all of us and especially to these children. Their innocence and their wisdom are met by your manhood in these photos and words to ease their mothers’ anguish, their breaking, overflowing, shattered and holding~all hearts. It’s a big thing, a very very big thing you’re doing in making space for all of this, a brand new gift as yet little seen, heard, touched, and felt and all the more enormous for not having been given in this way ever before. Thank you for bringing this to us all, for us all, Keith Harmon Snow.